In this post I am returning to the Women’s Jubilee Dinner of 1897, when one hundred women invited one hundred men to celebrate the progress of women’s work in the reign of Queen Victoria. As crime writers often say of their latest books, today’s post is part of a series but can be read as a standalone. You can catch up on Part 1, which gives an overview of the dinner, and Part 2 , which explores how well-known the attendees were, at your leisure.

There is a strong tendency to portray high-achieving women of the past as carving a lonely path. I set some parameters when I started the Women Who Meant Business project to create my ‘FT-She 100’ of early business women: they had to born in the reign of Queen Victoria and had at least some of their career in Britain. By focusing on a relatively short period of time and one country, I was hoping to identify communities as well as individual women.

So far I have found very few examples of women working in a state of isolation. Many were from supportive families and often had equally high-achieving sisters. Among the dinner guests were four sets of sisters: the artists Clara and Hilda Montalba; the Potter sisters, now Mrs Catherine Courtney and Mrs Beatrice Webb, both social workers; the high-achieving Garretts, Elizabeth, Agnes and Millicent; and a pair of scholarly twins you will meet later.

Other women had made lasting connections at university or within their professional community; or they found other women with shared interests. All of these dynamics are in evidence at the Dinner.

Two professions with a strong turn out were medicine and writing. The New Hospital founded by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, was a touchpoint for the fourteen doctors . The writers were part of a larger and more nebulous community encompassing fiction writers and historians, essayists and journalists. In May 1889, thirty women had gathered at the Criterion Restaurant for the first Literary Ladies’ Dinner. It had become a growing annual event; two weeks earlier, 120 women writers had sat down together and at least ten were also at the Grafton Galleries that night.

Women’s suffrage was a cause that bridged professional and, to some extent, political boundaries. Many guests were members of local campaigning groups that came together at the end of 1897 to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett. However, the women’s suffrage movement gets a LOT of airtime so I am going to look at four different places and organisations that between them show how curious and capable women could find community in the late 1890s.

First up is The Pioneer Club.

If you walk down St. James Street in Mayfair and along Pall Mall you will pass some of the oldest private members club in London: White’s, founded in 1693, Brooks (1762), The Reform Club (1836), The Travellers Club (1819) and The Athenaeum (1824). They admitted women as members in not yet, not yet, 1981, not yet and 2002 respectively. The progressive Albemarle Club (1874 was open to both men and women but was a notable exception.

Women had to establish their own meeting spaces. I would argue that the first women’s club was the Ladies’ Institute at 19 Langham Place, which in the late 1850s / early 1860s offered women a central London location where they could read, have lunch and go to the loo for a guinea a year. It had around 80 members. However, it was short-lived and usually the first women’s clubs are dated to later in the 19th century: the Somerville Club (1878), the Alexandra Club (1884), the University Women’s Club (1886). Writers were the first professional group to set up their own club in 1892. However, the most interesting has to be the Pioneer Club, founded, and largely funded, by Emily Massingberd in 1892.

The ‘essential qualification for membership was ‘an active interest in women’s progressive, educational, political or philanthropic societies.’ Two crossed axes formed the symbol on the official pin women could wear on their clothes to signify their membership. To try to eliminate social divisions, members were given a number when they joined, which was also used to organise the pigeon holes where their post would be left. Whether or not the Club actually delivered on its intent to be as welcoming to milliners as marchionesses is more debatable.

This desire for inclusivity was also reflected in Margaret Shurmur Sibthorp’s magazine, ‘Shafts’, which was launched later that year declaring itself to be ‘A Paper for Women & The Working Classes’. Its strapline was ‘Light Comes to Those Who Dare to Think’, its first issue included an article on the Pioneer Club and it reported regularly on its activities.

A dozen or so women at the Dinner had a connection with the Club. Lady Florence Harberton was on the committee. She was a champion of the Rational Dress Movement and a keen cyclist. Here she is in her cycling knickerbockers.

The suffrage campaigner Lady Elizabeth Cust, temperance advocate Lady Isabella Somerset, the writer Sarah Grand, economist Clara Collet and veteran suffrage campaigner Rose Mary Crawshay were all members.

In 1894 the Club had moved to Bruton Street, a two-minute walk from the Dinner venue. Kate Perugini, Sarah (Mrs Sheldon) Amos, Agnes Garrett and Millicent Fawcett were all at the opening party where they would have admired the portrait of Emily (now lost) by Louise Jopling, another Club member.

Maybe the Club was a topic of discussion that night. Emily Massingberd had died at the start of the year and the its future was in doubt, with a possible merger with the Grosvenor Club on the cards.

Next, on to Bloomsbury and the British Museum. ‘For some it is a workshop, for others a lounge; there are those who put it to the highest uses, while in many cases it serves as a shelter, a refuge, in more senses than one, for the destitute.’ So wrote Amy Levy in her essay ‘Readers at the British Museum’, published in Atalanta shortly before her untimely death in 1889.

The domed, circular Reading Room was a place where writers could reach for knowledge information for their research and a quiet place to write at no charge.1

The number of women applying for a Reader’s ticket rose markedly in the 1870s and 1880s as universities opened up. The Reading Room could accommodate 302 readers sitting at 38 banks of desks and women were meant to restrict themselves to the dedicated Ladies’ tables but they often oversat their marks. Beatrice Harradan, Beatrice Webb and Mary Kingsley are three of the women at the Dinner known to have been regular users of the Reading Room but there are bound to have been others.

Women could not be employed at the British Museum in curatorial or academic positions until 1919, when the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed. Before that, they were allowed to volunteer i.e. work unpaid – lucky them – and four women at the Dinner had done just that, giving lectures attended by the general public as well as scholars.

Leading the way was Jane Harrison, a Cambridge graduate and ‘the first woman in England to become an academic, in the fully professional sense – an ambitious, full-time, salaried, university and lecturer’, according to Mary Beard. Inspired by a lecture of Jane’s, Maria Millington Evans had read Classics at Oxford and had become an expert on Greek Dress.

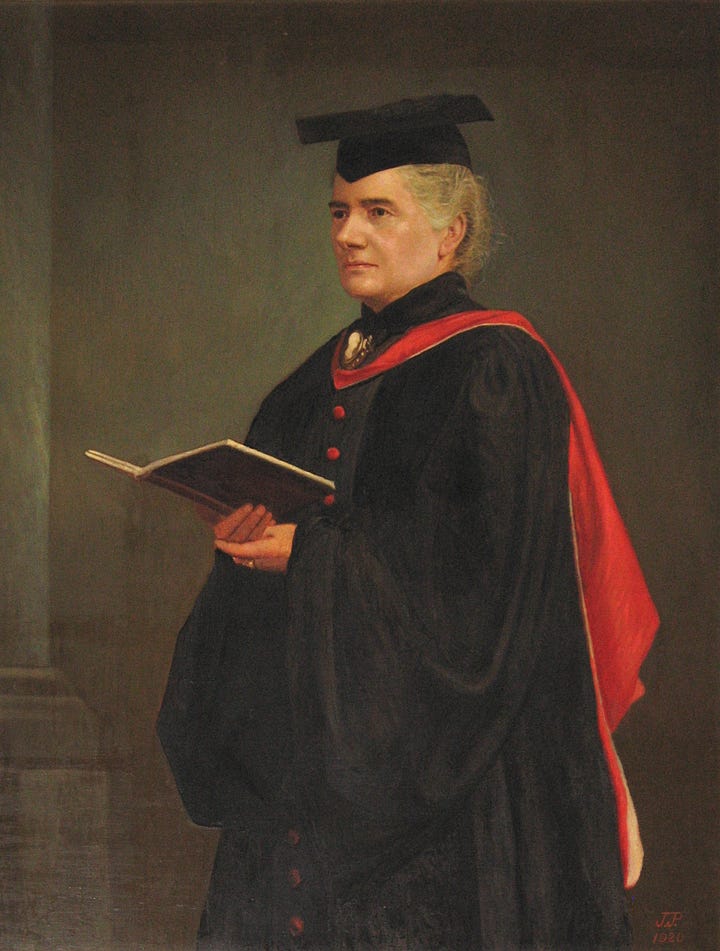

Emily Penrose was the first woman to gain a First Class Honours degree in Classics from Oxford. Now she was Professor in Ancient History at Bedford College. In 1907 she would be appointed Principal of Somerville College, taking over from Agnes Maitland (who was also at the dinner). Eugenie Sellers was a Girton girl, an archaeologist and art historian who later became librarian and curator at Chatsworth.

There was some crossover between the BM and the next stop on our network crawl, the picturesque town of Cambridge. The opening of Girton College in 1869 and Newnham College (co-founded by Millicent Fawcett) in 1871 meant women could study at the University even if they were denied a degree.

There were at least four more Cambridge graduates at the dinner besides the two classicists. Elizabeth Phillips Hughes had been a student at Newnham and now ran the Cambridge Training College (today known as Hughes Hall). The scientist Hertha Ayrton, Constance Jones, a philosopher, and Adelaide Anderson, now a prominent civil servant, had all studied at Girton.

Millicent and Henry Fawcett lived between London and Cambridge for ten years, between 1874 and 1884, the year of Henry’s death. His funeral in Trumpington had been attended by thousands, among them Catherine Courtney and Lady Harberton.

Many other Dinner guests had lived, or were still living, there because of the jobs of their husbands or fathers. Margaret Bateson, now a journalist at The Queen focusing on women’s employment, had grown up there thanks to her father’s position as Master of St. John’s College. Caroline Jebb, Louise Creighton and Agnes Smith Lewis had moved there with their husbands.

The wives of academics were an active and influential community. In 1886, May Paley Marshall (not one of the Dinner guests) had established the Cambridge Ladies’ Discussion Group, ‘to give ladies interested in social questions increased facilities for obtaining information and for hearing the views of those who have made such questions their special study’.2 Beatrice Webb’s research on dock workers was discussed there in 1889 and Clara Collet and Alice Westlake were among the many high-powered women and men who travelled up to Cambridge to speak at these public events.

Louise Creighton was on the committee for the first few years and in 1890 co-founded the Cambridge Ladies Dining Society, where the wives of academics could discuss their radical ideas in private. Caroline Jebb was another one of the twelve members.

Another lively discussion hub could be found on Chesterton Lane at Castle Brae, the home of widowed sisters Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson. Mary Kingsley was one of their visitors.

Neither had attended university but they had travelled extensively before their marriages and between them knew more than 12 languages including Arabic, Christian Palestinian Aramaic and Syriac. In 1892 they discovered the Sinaitic Palimpsest, the oldest known copy of the Gospels, in an Egyptian monastery and continued with their research up until the First World War.

Last up is the National Union of Women Workers (NUWW). If you are thinking factories, banners and strikes, that’s understandable, but for that, you needed to rely on the Women’s Trade Union League. The NUWW was constituted ‘with a view to bringing together women who are working either professionally or philanthropically…[it] will form a link for workers, whether philanthropic, educational or professional throughout the United Kingdom.’3

It sprung from a major conference organised in Birmingham in 1888 by the Women’s Liberal Federation, where one of the topics was women workers. There followed annual Conferences of Women Workers in Barnsley, Birmingham, Liverpool, Bristol, Leeds and Glasgow, growing all the time in attendance and scope. In 1895, a decision was taken to re-brand as the National Union of Women Workers and create a central organising committee. Here we again meet Louise Creighton, who was its first President.

With its liberal and progressive agenda, it is hardly surprising that at least ten of the women at the Dinner had been involved in these events in the preceding decade, including Beatrice Webb, Margaret Llewlyn Davies, Sarah Amos, Isabella Somerset and Lady Battersea; and that there a noticeable cross-over with the Pioneer Club.

This area of social reform was one in which many of the men at the Dinner were also engaged. The next time I return to the Dinner, it will be to look at some of the men who were there, who had invited them and the unexpected relationships that are revealed.

Thanks for reading! I love getting your comments so please keep them coming and share my work with abandon.

And finally, my recommendations..

Going out

Eileen Gray (1878-1975) was a superb craftswoman and innovative designer and architect who made a significant contribution to the modernist movement and then disappeared into obscurity until being rediscovered in the last years of her life. E.1027: Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea is a new documentary reconstructing her remarkable story.

Staying in

If you are interested in Cambridge history and have not yet discovered the Museum of Cambridge’s project, Capturing Cambridge, you are about to disappear into a glorious rabbit hole. There are stories, census results and projects associated with thousands of locations on its interactive map – have a browse.

Have a good weekend and see you in a fortnight.

Women in the British Museum Reading Room during the Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth Centuries: From Quasi- to Counterpublic in Ruth Hoberman Feminist Studies Volume 28 No 3 pp. 489-512

The Queen 2/11/1889

Letter to the Editor, Evening Standard 9/8/1895, Letter to the Editor

What a brilliantly clear and thoroughly researched piece, Lizzie, showing the interconnecting networks of these activist and pioneering women. Thank you for linking to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society!

I just loved the cycling Knickerbockers! All interesting and big thank you for the link to Capturing Cambridge, not a website previously known to me but having spent 6mths in the area way back in 1971, I shall explore with great interest.