In 1936, the Daily Mirror ran a series on high-achieving under-40s: who, it asked, are the ten young men and women shaping the future? Among their picks were Alfred Hitchcock, Kenneth Clark, Norman Hartnell, John Gielgud and….Betty Joel.

‘She is one of Britain’s leading designers of furniture and among the few women in the history of furniture designing who have touched anything like eminence in this most specialised craft.’ It forecast that in a couple of hundred years, collectors would be running after Joel furniture ‘as today they chase Chippendale or search for Sheraton’.1

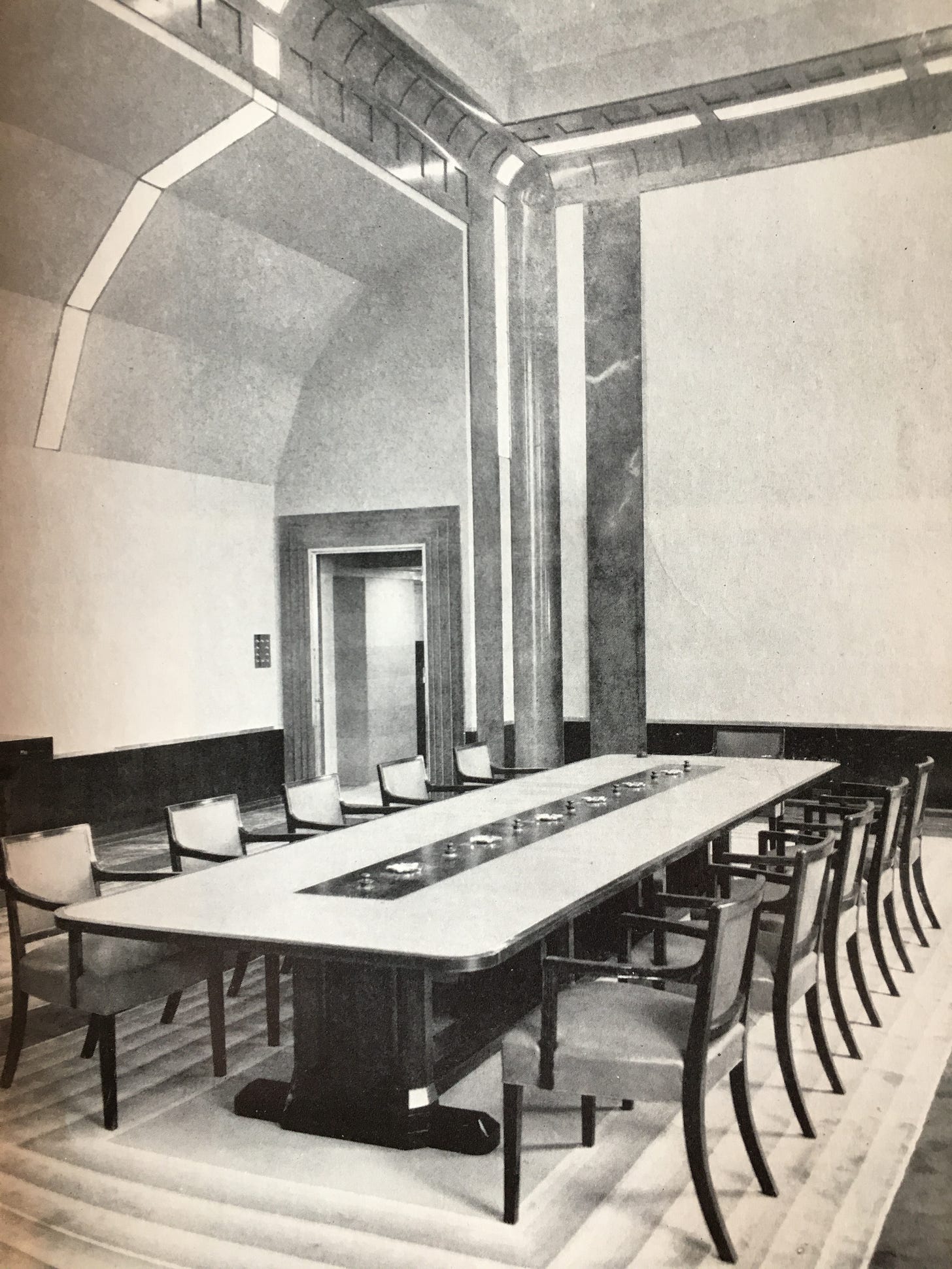

Betty Joel had actually just turned 42, but she was certainly riding high. She counted Lord Mountbatten and Winston Churchill among her private clients. Her furniture could be found in some of the most iconic buildings of the 1930s including the Daily Express building on Fleet Street, Shell Mex House on the Strand and Viyella House in Nottingham.

Betty Joel panelling adorned the walls of Coutts' Bank in Park Lane. Harley Street patients leant on her reception desk, Savoy Hotel guests and transatlantic voyagers on the RMS Queen Mary sat in her armchairs.

Yet, a year later she quit. So, who was Betty Joel? How did she build such a successful business? And why did she walk away?

Betty was a nickname and Joel was her married name: she was christened Mary Stewart Lockhart. She grew up in Asia, with five years of education in the UK in her teens and met her husband, David Joel, a naval officer, soon after she left school. When they married in Sri Lanka in 1918, David was 28 and Betty was 24. They needed furniture for their new house so Betty designed it and David built it.

A year or two later, the couple returned to the UK and settled on Hayling Island near Portsmouth. They built their own cottage there. More furniture was needed so Betty got to work. Friends who visited the house started to make requests and in 1921 the couple set up a furniture manufacturing company. Even though this was a partnership, they wanted to create a differentiated brand with strong appeal to women and so called the business Betty Joel Ltd.

More than a Token effort

Betty Joel used teak and oak in her first line of furniture so called it Token. It was launched at the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition in Olympia in March 1922. Exhibitions were an important business development channel for Betty: writing in 1935, she said that ‘in fourteen years I have spent hours which total up to nearly a year of my life on exhibition stands so I know what the public want.’2

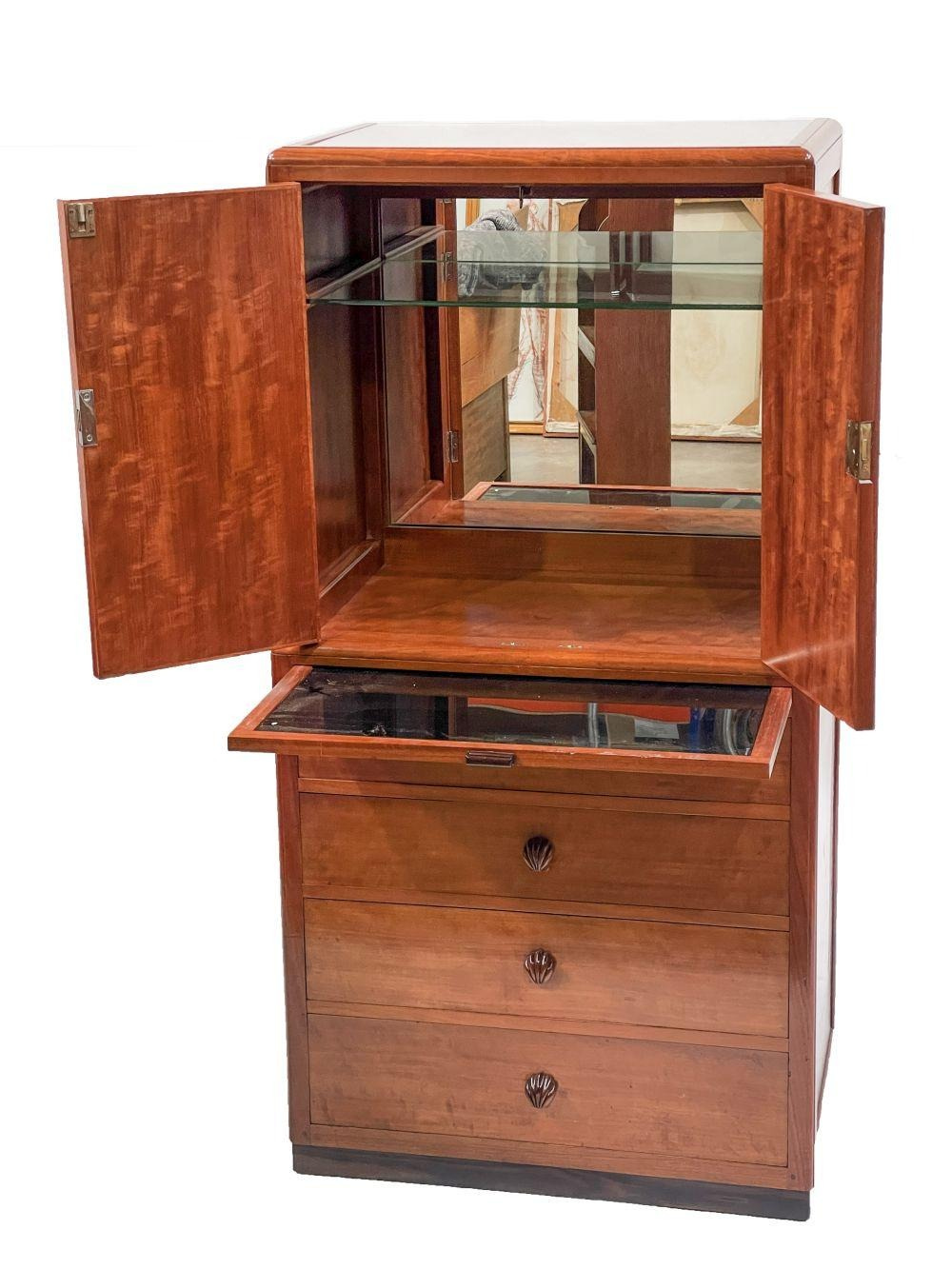

She started with function. John Gloag, the design writer, commented as early as 1925 on her ability to find fresh and simple solutions to various problems.3 The drawers of dowry-chests were lined with cedar as a natural defence against moths. She replaced handles with streamlined ‘finger sockets’, a feature that seems commonplace today but was innovative then.

Dressing tables had built-in lighting, glass tops made it easy to see what was in the drawers underneath and stools slid underneath. Other space-saving ideas were bathroom stools that doubled as laundry baskets and fold-out tables that masked radiators when not in use.

Once she was happy with the design, she used carefully-chosen polished wood rather than decoration to create a piece of desirable furniture. Over her career she worked in walnut, sycamore, cherry mahogany, Queensland silky oak and Canadian pine as well as oak and teak.

Betty was attractive and stylish, with a slim build, reddish-gold hair and deep blue eyes. She featured in her own promotional material, leaning up against mirrors or sitting down at a dressing table and her story had wide cross-appeal: high-society magazines were interested in her family connections and dress sense; the tabloids highlighted how the lack of ornamentation in her furniture made it quick and easy to dust.

Picking up pace

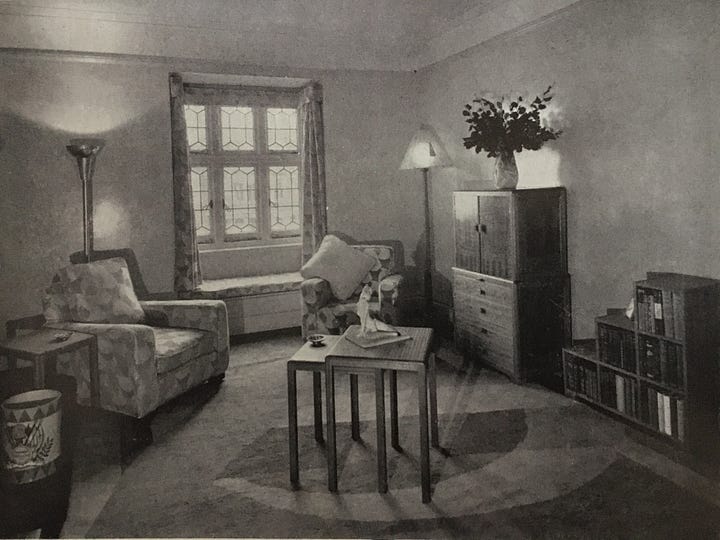

By 1924, Betty and David were able to open their first London store at in Chelsea and in 1927 they moved to a much larger location at 25 Knightsbridge. A bright yellow front door opened up to reveal furniture displayed in a dozen rooms, carefully styled with rugs, lighting and curtains. Betty and David had a flat on the upper floor that acted as an extension of the ground-floor show room and featured in magazine articles.

Clients could request changes to the size and colour of furniture on display. Although Betty designed rugs and carpets, she never ventured into textile design so she and David sourced fabrics from France to create unique upholstery. Their distinctive delivery van had a Rolls Royce bonnet and was painted bright yellow and blue with Betty Joel emblazoned in large letters on the side.

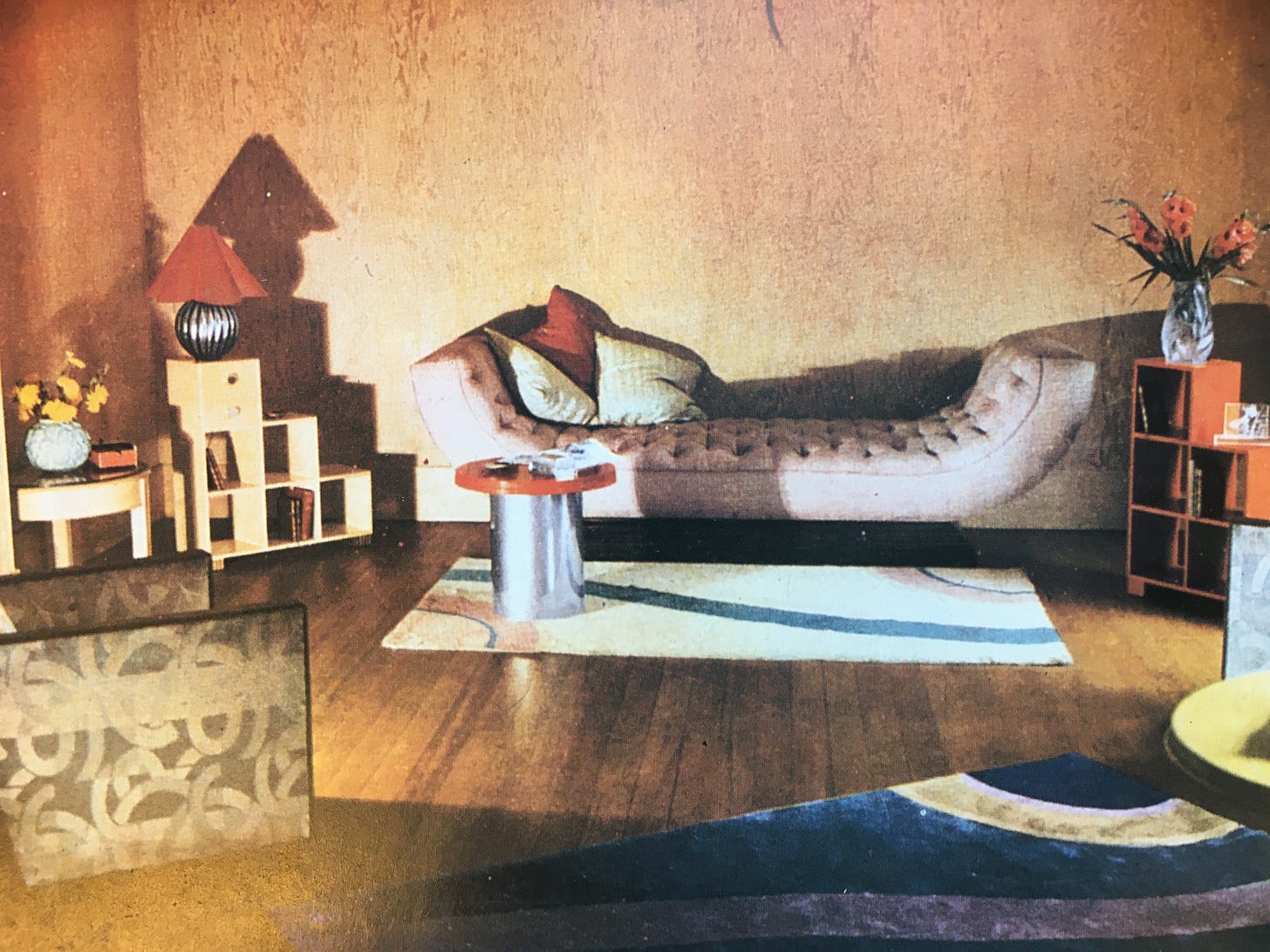

The 1930s saw Betty moving more firmly into the area of interior design. In 1932, she designed a four-room show apartment overlooking Park Lane, its walls lined with ‘sumptuous’ polished wood panels. Derek Patmore described her as ‘one of the most important figures of the British school of decoration’.

Although she created show rooms and even show flats, she expected consumers to express their personalities by mixing the old with the new, putting cherished possessions alongside newer pieces. She was no fan of the totalitarian approach favoured by Mies van der Rohe, Erno Goldfinger and Serge Charmayeff.

‘I discern an unfortunate tendency in some contemporary architects…They seem so convinced of the perfection of their taste, so sure of their views on what constitutes a perfect home, that they insist on designing everything about the house from the weathervane to the bath tap, from the dinner ware to the waste paper basket.’4

She wanted to work with architects who gave designers freedom to create furniture for their buildings and found one in Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel (1887-1959). They collaborated on several projects, including St. Olaf House in London Bridge, the headquarters for the Hay’s Wharf Company built between 1928 and 1932.

Goodhart-Rendel designed a new shopfront for 25 Knightsbridge and a grand new modernist factory in Kingston-upon-Thames, which opened in 1934, Betty Joel writ large on the outside.

Brand building

Betty raised her profile further by writing about design, in newspaper columns, magazines and books. Many firms wanted her to design products for them but here she was less interested in the brand benefits than the commercials. One company that clearly paid properly was Kolster-Brandes Ltd and both parties benefited.

The radio she designed for them, in walnut bound with chromium-plated steel, was ‘one of the sensations’ of Radiolympia in 1933. They sold 2,500 sets sold on one day alone. Even the Duchess of York bought one. That year Betty was featured along film stars as one of the highest-earning women in the country, earning £5,000 a year (equivalent to c.£365,000 now).

Betty later dismissed anyone attempting to label her a feminist – ‘I was simply a woman doing business’, she would say. Although she had a good relationship with her long-standing assistant, Ella Adler, she and David did not employ any women in their furniture factories and there is no evidence of Betty participating in any of the many business women’s networks in London.

She collaborated with women, notably Marion Dorn and Anna Zinkeisen, (the only other woman on the Daily Mirror’s Under 40 list), but did not make a particular point of it. However, there was a gallery space in the Knightsbridge store, which Betty used for a solo shows of women artists and in 1937 she celebrated the Coronation with work by Dorn and Zinkeisen featured alongside Dame Laura Knight, silk-maker Zoe Hart-Dyke and Eileen Hunter, an up-and-coming textile designer.

Exit stage left

The success story had an abrupt end. In 1936 Betty’s sister, to whom she was very close, died and the following year she also lost her father. With her marriage to David unravelling, Betty decided to walk away from both him and the business.

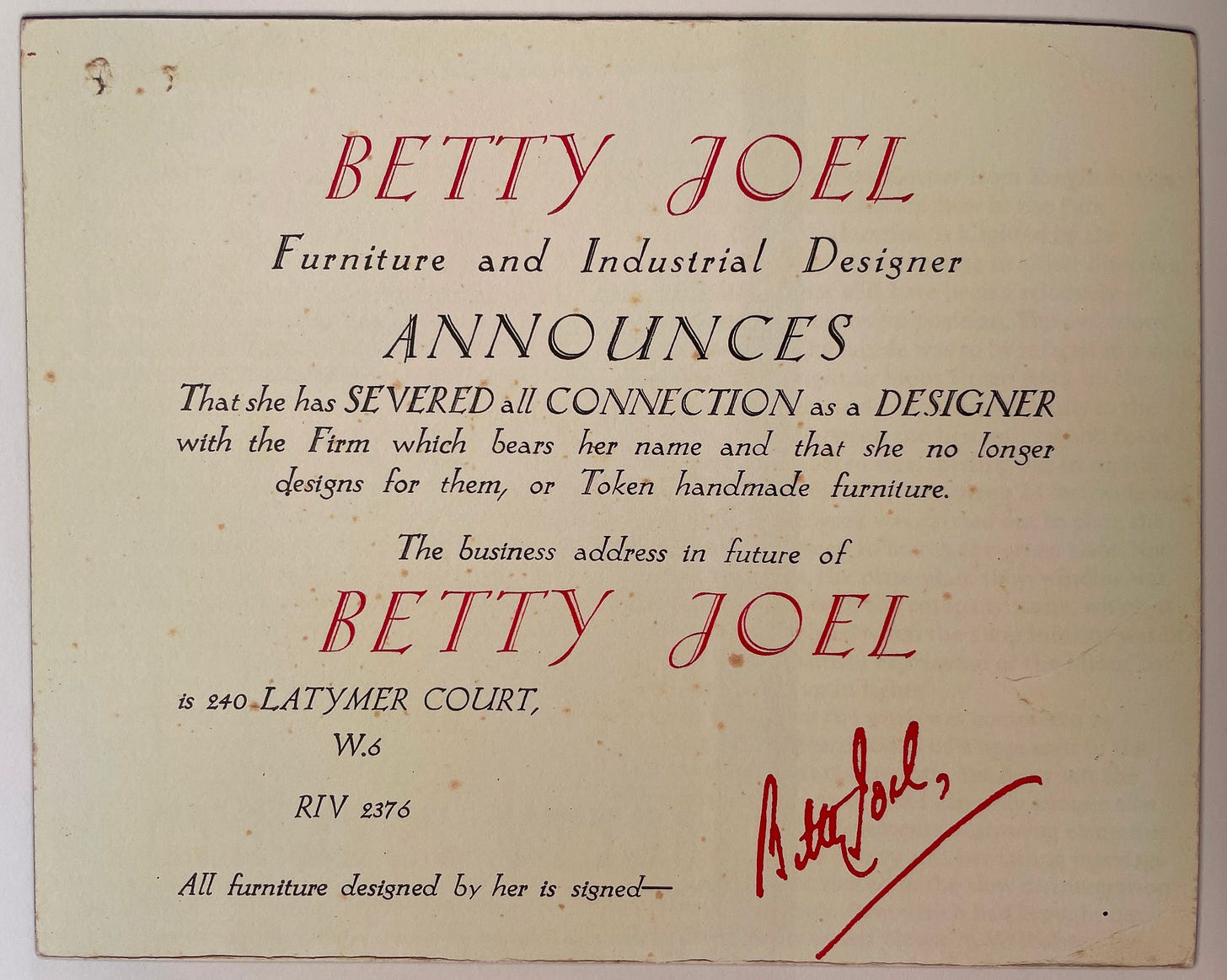

The retail arm was wound up and David purchased the factory to sell furniture to the trade under his own name, David Joel Ltd. Betty reverted to her maiden name and never did any more design work.

Despite David writing books on furniture in the 50s and 60s where he devoted ample space to the work of the partnership, the name of Betty Joel soon faded from the annals. I discovered her through a book on ‘The Decorative Thirties’, written in the early 1970s, which devoted nine pages to Syrie Maugham but said nothing about Betty to supplement three photographs of her furniture.

Why? I have some theories.

There are a number of dominant design trends in the 1920s and 30s: Bauhaus, Modernism, Art Deco, Vogue Regency. Betty’s view of good design was making ‘something so unassuming that when you live it, you do not get tired of it’ and her style does not fit neatly into one of these categories.

Some women have come back into view because of their work with a ‘great man’. Lilly Reich is a good example. Betty’s design partners were many and various and did not include the big name architects of the inter-war period.

Brought up overseas, Betty was a social outsider. Self-taught, she was not part of any art school gang. She was never a member of the Cecil Beaton crowd or part of the Bloomsbury set and was too busy working to be a Bright Young Thing. She did not have a racy private life helpfully recorded in a diary or letters. Had any of these been the case, I suspect Betty Joel would already be a familiar name.

However, in the end quality usually wins out and so it is here. Now Betty Joel furniture is back in the auction room and a dressing table could cost anything up to £4,000. It is only ninety years since the Daily Mirror made its forecast: there is plenty of time for that journalist to be proved right.

Thanks to Clive Stewart-Lockhart, great-nephew of Betty Joel, for the help he has given with my research. He has just been published a comprehensive book about her life and work: you can find more information here.

For my recommendations this time, I am going to continue the inter-war theme.

Going out

If you missed ‘Vanessa Bell: A World of Form and Colour’ at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, you have a second chance to see it at Charleston in Lewes. It is a

Staying in

Dezeen has published an excellent series of articles about Art Deco to celebrate its centenary so put aside a few minutes to have a scroll. There is a useful ‘quick guide’ with features lovely images of Betty Joel’s furniture, and the work of the American muralist Hildreth Meière (1892-1961), a welcome new discovery for me.

Thanks for reading! It’s always lovely to get feedback whether you hit the like button or leave a comment. If you’re not already signed up, you can subscribe for free to get regular newsletters and support my work.

Next time I will be returning to the Women’s Jubilee Dinner so if you missed Part 1, have a read now. And you can always find more profiles of brilliant women at the dedicated site, Women Who Meant Business; or follow me on Instagram.

Daily Mirror 18/6/1936

‘A House and a Home’ by Betty Joel in The Conquest of Ugliness (1935) ed. John de la Valette

‘Time, Taste and Furniture’ by John Gloag (1925)

‘A House and a Home’ by Betty Joel, ibid

What beautiful furniture! I have desk/chair/bin envy. Thank you so much for featuring this amazing woman.

well written and lots of visuals supporting the story well- love the desk !

also thanks for adding the link to the quick guide, learned a lot about art deco from this brief summary, very useful