Welcome to Women Who Meant Business. On Saturday mornings, once every two weeks, you can enjoy stories about entrepreneurial women and get ideas about other things to see and do. Happy reading.

I recently wrote an article for Boundless magazine about the influence of two literary agents, Audrey Heath and Nancy Pearn, on modernist literature. The story featured the writer Radclyffe Hall.

I wanted to find a photograph of her partner, Una Troubridge, so I searched the National Portrait Gallery collection. ‘Sitter, associated with one portrait’, it said. Next to the entry was this image. I looked at it, confused, thinking ‘but that’s Radclyffe Hall.’

Then I read the title of the photograph. Sure enough, there in the bottom left-hand corner you can see Una’s left eye, a beautifully-shaped eyebrow and a small section of her chic bob.

It made me think about some of the business women I have written about, nominally represented but effectively barely visible. One is the designer Lucy Duff Gordon (1863-1935).

The Victoria and Albert Museum holds the archives for Lucile, the couture house she founded in 1893. As well as a few of her gowns, they have 58 files of photographs, sketches and press cuttings. Some of these items can be seen in the Collections online. However, if you visit the V&A’s Fashion Galleries today, this is the only reference you will find:

The caption reads: “Photograph, Heather Firbank wearing Lucile evening dress, Rita Martin (1875-1958) 1912”. There is more information about the woman who took the photograph than the one who designed the dress, the woman who was the world’s first international couturier. Not just the first woman, the first full stop.

Lucy opened Maison Lucile in London in 1893, when she was 30 and still Mrs James Wallace, a single parent with an eight-year-old daughter. By 1910, she was able to take her brand across the Atlantic and took New York by storm. The following year, she floated the idea of setting up a branch in Paris. Her friends in France thought she was over-reaching.

They threw ‘a douche of cold water over my enthusiasm’, she later wrote. She ignored them and her three-day launch event in May 1911, complete with a live orchestra and an endless supply of tea, was a smash. At the height its popularity, Lucile Ltd employed around 2,000 people.

Women loved wearing Lucile. Lucy stripped out boning, so they were lighter, and put splits into the skirts to make it easier to walk in them. Her dresses were slightly racy, with low necklines, and the layers of fabrics and colours combined to magical effect.

The details were exquisite - buttons, lace, ribbon, tiny silk rosebuds and delicate bows. As she built her business, she tapped into a rich vein of fin de siècle decadence and she maintained her pre-eminence in the early part of the 20th century.

But it was her innovative approach to publicising, marketing and selling clothes that has left a lasting mark on the world of fashion as we know it today.

What did she do that was so remarkable?

She invented the catwalk show.

On 27th July 1904 the cream of London society crowded into a long, grey-walled Georgian room in the Lucile salon on Hanover Square. At one end was an empty platform. As the audience clutched their programmes, a band started to play, flashes of lime-light came from the wings and girls appeared in Lucy’s creations.

They ‘sat, turned, twisted and twirled and finally walked down the room between rows of spectators to show themselves and the gowns they carried, off to the best possible advantage’.

The sense of theatre was enhanced by the programme. Gowns were divided into sections: ‘For the Dinner Party’; ‘The Cult of Chiffon’; and were given extravagant or suggestive names: ‘Spring’s Delirium’; ‘Incessant Soft Desire’; ‘Red Mouth of a Venomous Flower’. Lucy was the first designer to bring together fashion and performance. She should be known for this, if nothing else.

She created the super-model.

‘Curious to relate’, said the writer Marie Corelli, who witnessed Lucy’s first fashion show, ‘there were quite a large number of “gentlemen” at this remarkable exhibition of feminine clothes. From then on, men were as eager as women to get hold of a ticket and there was little mystery as to why.

To show off the clothes to their best advantage, Lucy had gone out to scout models. She searched for tall, striking young women, taught them how to walk and gave them stage names like Gamela and Dinarzade.

One, Kathleen Mary Rose, who was born in Wimbledon in 1893, started modelling for Lucy when she was 17 under the name of Dolores. While her height, nearly 6ft, made her stand out, it was her haughty attitude and refusal to smile that set her apart. In 1916, she was spotted by Florenz Ziegfeld in one of Lucy’s New York shows and the following year he put her in his show.

Dolores went on to become one of the best-paid Ziegfeld Follies but ‘retired’ (aged 30!) after her marriage in 1923. She and her husband moved to Paris and during the Second World War were active members of the French Resistance.

She sold the experience.

‘Dwell time’ is a key measure in retail: the longer customers linger, the more they buy. Lucy intuitively understood this and made her salon a place women wanted to hang out. They could sit on sofas, drink tea, play cards and catch up, all the while viewing the latest Lucile collection.

The brand was particularly famed for sexy underwear in soft shades. When Lucy moved to larger rooms on Hanover Square in 1902, she created a Rose Room dedicated to looking at lingerie, with a luxurious day bed. She made this a feature of her salons from then on: pictures survive of those in New York and Chicago.

She gave fashion a new stage.

Lucy clearly loved performance and embraced the world of entertainment and seized opportunities to design looks for both stage stars and screen sirens. We are all familiar with the iconic image of Audrey Hepburn in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ in her Givenchy dress. Lucy was creating the same iconic looks decades earlier.

Cecil Beaton fell under the spell of the actress Lily Elsie in 1907 when she was wearing a costume designed by Lucy. A later successful partnership was with the dancer and film star Irene Castle. Hers is a name few would recognise today, but such was her influence in 1915 that when she cut her hair, thousands of women rushed to their hairdressers for the “Castle Bob”.

Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson, Marion Davies and Lilian Gish all appeared on screen in Lucy’s designs. If walking the red carpet had been a thing in the 1910s, many of the biggest stars would have been wearing Lucile.

She embraced mass fashion.

In 1917, Lucy made a deal with Sears Roebuck to create a ready-to-wear line for their catalogue business. ‘I am getting dead sick of working for the “few” rich people with their personal fads… I am going to work for the millions’, she wrote to her daughter, Esme.

Women across the United States could get an off-the-shelf Lucile dress at a tenth of the designer price. The partnership ultimately failed due to legal issues arising from another partnership agreement Lucy had signed but it foreshadowed the partnerships between couture labels and the high street so familiar today.

So why do so few people know Lucy’s name? Not many of her dresses have survived, certainly not enough to create an exhibition of any scale. When I have seen one on display, it has always been as part of a larger thematic show.

However, I think the bigger problem is that her clothes don’t mark an obvious turning point in the history of dress. There is no single Lucile garment to stand alongside a modernist design by Paul Poiret from the 1910s, a Chanel suit from the 1920s, a New Look skirt from Dior’s 1947 collection or a Mary Quant mini-dress. Lucy’s lasting impact was not on what women wore but how the fashion industry worked.

On 31st May, the V&A East Storehouse will open in Stratford. It promises a new way of showing archive material with 100 mini curated displays. I have my fingers crossed that one focuses on the brand of Lucile and the woman who built it. Keep your eyes peeled.

If this has made you curious about Lucy, I have written more about her as part of the Women Who Meant Business project, including how she got started, her relationship with her sister, Elinor Glyn, her survival of the sinking of the Titanic and why her business collapsed. You can also find the sources I have drawn on for this piece.

In other news..

If you want to go out..

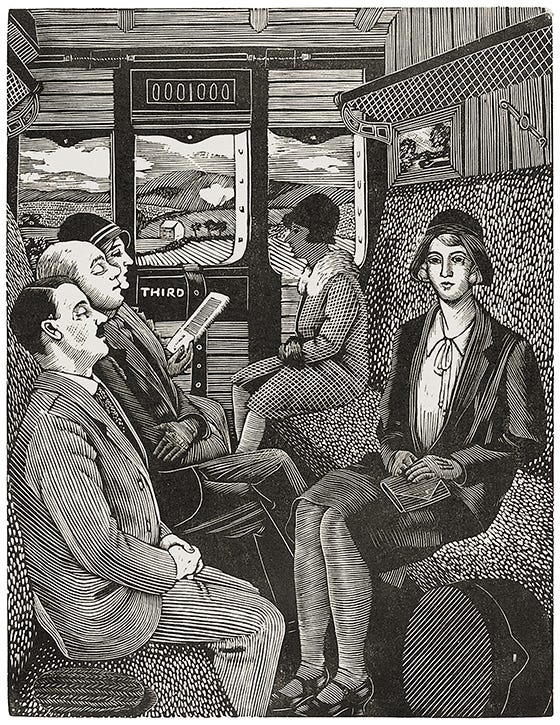

The Dulwich Picture Gallery is showing the work of Tirzah Garwood (1908-1951), the first major exhibition devoted to the artist and designer. She was multi-talented, making wood engravings, marbled wallpapers, oil paintings, collages and embroidered works.

The show had passed me by until I read this piece by Jane Brocket which made me want to go. I have since discovered a loose connection to another woman I’ve written about, Marion Dorn: both women contributed to the decor of the iconic Midland Hotel in Morecambe in the early 1930s. I’ll be interested to see what else I discover. The exhibition runs until the 26th May.

If you want to stay in..

Jane Robinson’s brilliant biography of Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827-1891) is out in paperback this week. A woman with plenty of resources and enormous energy, Barbara Bodichon played a pivotal role in the Victorian feminist movement. She campaigned for women’s suffrage, women’s education (co-founding Girton College, Cambridge) and the right for women to join the professions.

She was an artist and a consummate networker. Visitors to her home in Sussex, Scaland’s Gate, inscribed their names around the fireplace. By the time of her death there were around 300, including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Jane and William Morris and Marianne North.

Whether or not her name is new to you, you will enjoy discovering more about her remarkable life.

That’s it for this edition - thanks for reading! Do share your feedback by hitting the like button or leaving a comment. Subscribe for free to stay up to date and support my work.

Look for the next edition on Saturday 8th March, International Women’s Day. In the meantime you can find more profiles of brilliant women at the dedicated site, Women Who Meant Business; or follow me on Instagram.

Fascinating! Women I have never heard about till reading here - Lucy Duff Gordon definitely caught my interest.

I came across Lucy Duff Gordon when I was researching the life of Nelly Erichsen, who was a collaborator and sometimes a friend (not always!)of Janet Ross, born Duff Gordon. I loved the Titanic story....https://open.substack.com/pub/harkness/p/the-quite-extraordinary-mrs-ross?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=gqpmg